Two University of Florida College of Pharmacy faculty members finally convinced the FDA that a widely used nasal decongestant does not work.

By Matt Splett

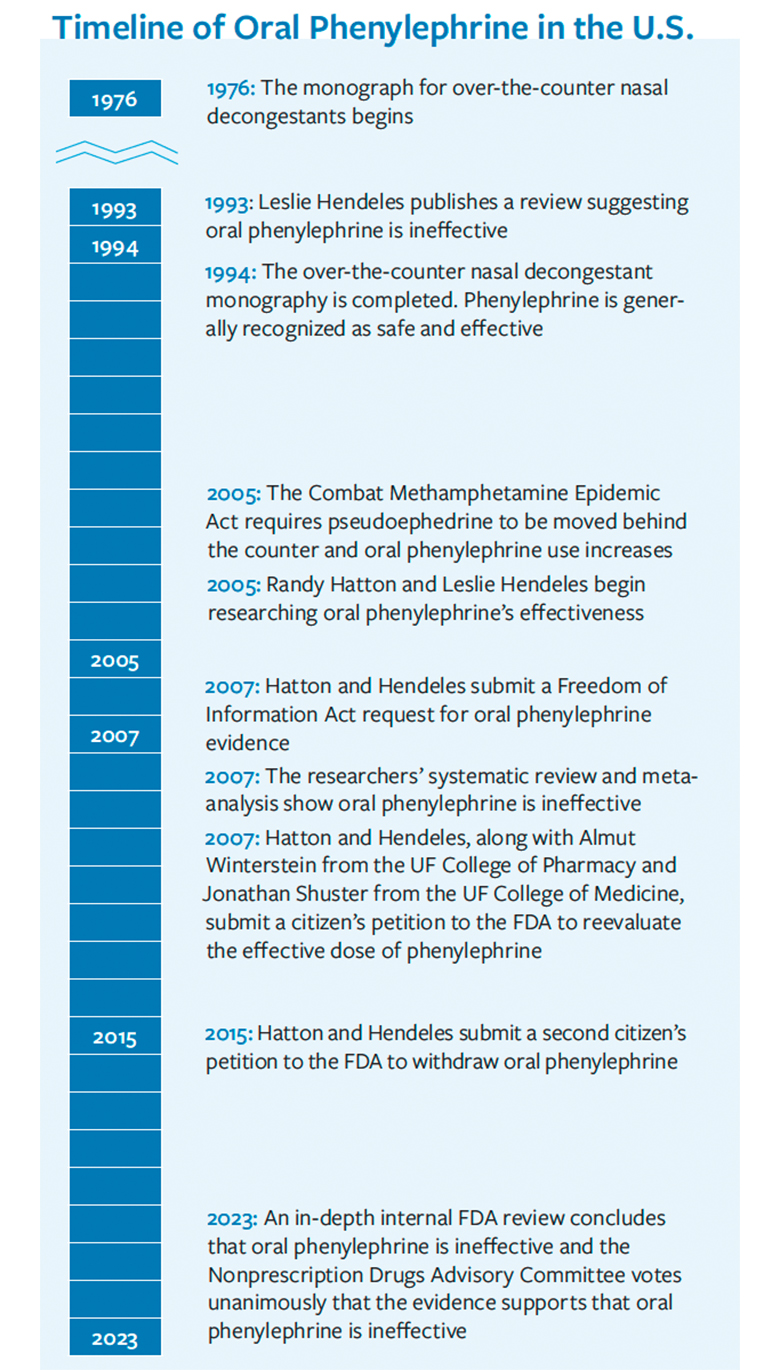

Phenylephrine is a popular ingredient found in more than 260 over-the-counter cold and allergy medicines. Drug makers have long contended that it helps clear nasal decongestion—but two professors from the University of Florida College of Pharmacy spent two decades refuting that claim. Backed by science, they finally convinced the FDA that the common nasal decongestant does not work.

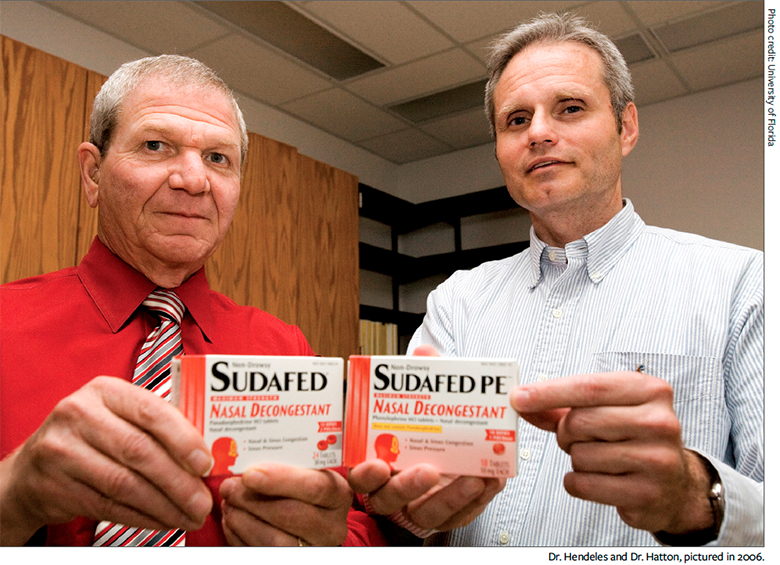

In 2005, Dr. Randy Hatton was co-directing the Drug Information Center at UF Health Shands Hospital when questions about oral phenylephrine began flooding the phone lines. Pharmacists and physicians from around Florida were calling the center asking if oral phenylephrine worked and what dose to take.

A federal law enacted that year mandated retailers move pseudoephedrine products behind the counter to combat illicit methamphetamine production. Pharmaceutical manufacturers reformulated common cold and allergy medicines using phenylephrine instead of pseudoephedrine. Yet, skepticism emerged within the healthcare community regarding the effectiveness of oral phenylephrine. “The Drug Information Center fielded many similar calls questioning whether oral phenylephrine worked as a decongestant,” said Hatton, a clinical professor in the college. “The UF College of Pharmacy students and residents staffing the center would examine the literature to provide informed responses to the healthcare professionals. In the case of phenylephrine, they did not have to look far for an answer.”

In 1993, Dr. Leslie Hendeles, a professor of pharmacy in the UF College of Pharmacy, published a review paper in the journal Pharmacotherapy addressing the choice of decongestants and mentioned the ineffectiveness of oral phenylephrine. While the drug posed no safety risks, he referenced earlier unpublished studies suggesting phenylephrine’s resemblance to a placebo, with it being inactivated in the gut during the first pass through the liver resulting in little of the drug reaching the bloodstream.

Hendeles and Hatton met one day to discuss their suspicions about phenylephrine. As academic pharmacists, they prioritized evidence-based approaches to ensure the safety and efficacy of drug therapies for patients. They left the meeting with a mutual determination to investigate the inefficacy of oral phenylephrine and share the evidence with the FDA.

The 20-Year Journey

For almost 20 years, the endeavor to persuade the FDA of the inefficacy of oral phenylephrine encompassed extensive research, editorials, citizen petitions and advocacy efforts aimed at influencing policymakers and public sentiment. Hendeles and Hatton acknowledge they may have been a bit naïve at the beginning, believing the task would be straightforward. Nevertheless, as the journey unfolded, their commitment to the cause never wavered. “Every time new evidence emerged that supported our assumptions, it would reignite us,” said Hendeles, now a professor emeritus in the college. “We were committed to the issue and viewed our efforts as a public service.”

In 2006, Hendeles and Hatton published their first editorial in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. They contested the FDA’s endorsement of the 10-milligram oral dosage approved in 1976, citing inconclusive evidence to support phenylephrine’s effectiveness in alleviating nasal congestion. A few months later, Hatton submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the FDA. They sought all the available data employed by the agency in evaluating the safety and efficacy of oral phenylephrine.

“We were able to use all that information and do a systematic review and meta-analysis to support what Leslie had published in 1993 and what pharmacists were calling the Drug Information Center and reporting that oral phenylephrine did not work,” Hatton said.

Dr. Russell McKelvey, a pharmacy resident at the UF Drug Information Center, contributed to the systematic review and meta-analysis that was published in 2007. The same year, Hendeles and Hatton filed their first of two citizen petitions asking the FDA to reevaluate the dose of phenylephrine. They thought a higher dose might compensate for the poor absorption. The move spurred the FDA to form a Drug Advisory Committee to review phenylephrine’s effectiveness, but the panel ultimately decided more data was needed before a decision could be reached.